Human beings hate change. All of us.

When Zoom has to update right before an important call, I'm not thinking "yay! an update! I'm

thinking, ah. I don't have time for this. I just want to do my call."

And I'm an innovation expert.

When Midwest express stopped serving cookies or Southwest Airlines stopped serving peanuts,

I wasn't cheering for the future of airline food. I didn't like it. I was used to the way it was.

So telling people to embrace change is just telling them to fight natural human instincts. We

prefer stability and predictability.

So what do we do instead?

Instead of trying to convince everyone love change, why don't we equip them with the tools

and mindset to navigate it. So that the change isn't as upsetting or disruptive. And they

approach it with an open mind.

There are two Master Skills that innovation experts share in this regard: Learning Agility and Growth

Mindset.

But why are these skills so pivotal?

Because they don't just prepare individuals for one change; they prepare them for the ongoing

journey of change. They foster adaptability and instill a sense of curiosity.

Working on these skills outside of a big change initiative reduces the intimidation of that future

change when it becomes necessary.

(Posted 9.9.2023)

I have a big new goal I've been coveting, and I thought I would document my journey from the very beginning.

I recently learned of the Maccabean Games or the Jewish Olympics. It is the third largest sporting event in the world, after the world cup and the actual Olympics. 10,000 athletes go to Israel every 4 years to compete in Olympic events. And the best part is there are age groups!

Ever since I learned about this event, I've wanted to try to go. Having never had a chance to participate in sports as a kid, and really enjoying both sports and competition, this feels like a perfect goal.

Goal: To try to make it to the Maccabean Games (by qualifying for team USA) in tennis. 😮

Now. Here are all the reasons I've been telling myself to forget it.

1. I started playing tennis this year 😂. And the level I have to get to is likely that of a collegiate player. Is that even possible??

2. I had breast cancer surgery last year that sliced through my pectoral muscles. Could I ever get them back strong enough to be competitive?

3. I'm 42 and already experiencing some pain in my knee and hip after exercise. Can my body even handle the training it would take?

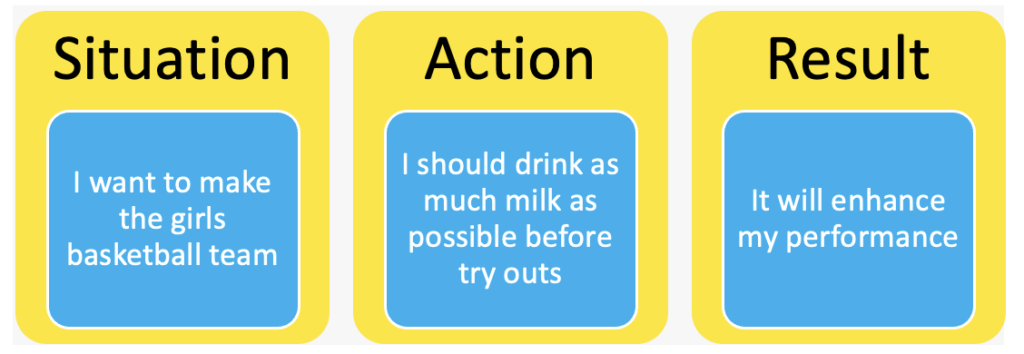

4. I've never actively played a competitive sport in my life. And those of you who know my funny high school basketball tryouts story know that I would basically be starting from scratch 🥛🥛🥛.

And here's my short list of why I should do it:

1. I think I can do it.

2. It would be fun to try ❤️.

3. I love playing tennis and can't seem to get enough of it.

Ok. Tell me everything I need to know!

(Posted 9.16.23)

I think it's easy to look at a big, audacious goal and think, "Where do I even start?"

As someone who thrives on challenges, you may have seen my new goal: Improving my tennis rating from 2.5 to 4.5 within a year and qualifying to represent Team USA at the Maccabiah Games in Israel!

Here's how I approach such monumental tasks:

1. Break it Down: Big goals can be intimidating. I start by breaking them into smaller, more manageable tasks. In terms of tennis, it's about improving specific skills one at a time - be it the serve, the volley, or the footwork.

2. Seek Expertise: It's important that I (a person who knows almost nothing about tennis) am not in charge of creating the game plan. That's why I got a coach. He knows what we need to work on to achieve the goal and he provides deliberate practice (the kind of practice that improves skill).

3. Find The Believers: In moments of doubt (and they come often), it's the cheerleaders in our life who reignite our flame. I'm grateful for friends and fellow enthusiasts who remind me of my potential when it seems like an impossible goal. (HT to Adam Smiley Poswolsky for teaching me about the importance of Believers).

4. Identify the Good, Better, Best Goal: I got this strategy from Jon Acuff. It helps you not set yourself up for failure when attempting something really ambitious. I'm creating three options of what I'd like to achieve: Good: I train for a year without hurting myself and significantly improve my rating to 3.5 or higher. Better: I place in a competitive tournament. Best: I place in the US qualifier for the Maccabiah Games.

5. Measure Progress: I'll be setting milestones along the way and sharing them publicly. By tracking where I am vs. where I need to be, I can make adjustments.

6. Don't Over Do It: Passion is a double-edged sword. While it drives you to train, it can also cause burn out or risk injury. So I've recruited a physical therapist to the team to make sure I'm not taking myself out of the game by going too hard to fast right off the bat.

To my tennis enthusiasts out there, I'd love any tips or insights you might have. And to everyone else, what big goals are you setting for yourself? Let's Go Big together! 🌟

(Posted 9.23.23)

When we set big goals, our natural impulse often urges us to dive in headfirst, relying on sheer force to propel us forward.

However, I believe in the value of sitting with a problem and asking a lot of questions up front to help you chose the highest ROI for your energy.

The biggest challenge with doing something new is innovation waste, or using all that energy in ways that don't really move the ball forward.

Take my own objective: I've set an ambitious target to achieve a 4.5 tennis rating in a little over a year and qualify to represent team USA in the Maccabiah Games.

Rather than blindly enrolling in intense training sessions, I'm pausing to ask all the questions:

Foundations & Basics:

- What are the fundamental techniques every tennis player should know? (Below is a video of me spending a day learning the volley).

- How do I avoid typical beginner mistakes?

- What equipment do I need? (did you know there are actual tennis shoes?? And they aren't your sneakers 😂)

Training & Practice:

- How often should I practice to achieve my goal and not injure myself?

- What drills are most effective for building foundational skills?

- How will I know when I'm ready to compete in tournaments?

Mentorship & Guidance:

- How will I know when my coach has topped out at what they can teach me?

- Are there different coaches that specialize in teaching various fundamental skills? Or those that teach singles vs doubles players? Or even those that teach women vs men?

- Who can I talked to that has not only qualified but done well at the Maccabiah games so I can learn from them?

Physical & Mental Conditioning:

- How can I improve my agility, strength, and stamina for tennis?

- What kind of content would be most helpful for me to consume in between lessons? Books, Youtube videos, Instagram accounts.

Feedback & Improvement:

- How can I get regular feedback on my techniques and gameplay?

- What's the best way for me to record my practices?

- Are there other tools or technologies that can assist in helping my performance?

Tournaments & Competitive Play:

- Which local tournaments or leagues should I consider joining?

- How should I prepare for matches, and how do I best learn from each competition?

Community & Networking:

- How can I build relationships with players at or above my skill level to challenge myself?

_____________________________

Do you see how starting with questions can help you save a lot of time and effort?

My hope is that this curiosity fueled approach will set me up for success.

And to anyone embarking on a new ambitious goal: Don't start with a plan; instead, start with a list of questions you want to figure out!

#growthmindset#innovation#drinkmoremilk

(Posted 9.30.23)

In my journey from a 2.5 to a 4.5 tennis player, I've learned a profound lesson that goes beyond the tennis court: The immense value of deliberate practice.

It would be easy for me to spend hours on the court, hitting ball after ball, hoping to improve. In fact, that's how I spent my spring and summer.

While time and effort are commendable, they alone aren't enough for substantial growth.

That's where the magic of deliberate practice comes in.

Deliberate practice is a concept that was popularized by Anders Ericsson, who studied the habits of top performers across various fields. Ericsson's research showed that with the right type and amount of practice, most people can achieve exceptional levels of skill and performance in almost any domain.

But it only works if you follow this very specific kind of practice (I outline the steps in the comments below).

I had my first lesson with a coach about 3 weeks ago, and my body was so sore after that I kept saying, "what have I been playing all this time???" My body was just not used to the movements he was asking me to do!

That's my coach Elliott, in the picture.

🌟 Improving Alone vs. With a Coach:

When trying to improve on our own, we rely heavily on self-assessment, which can often be clouded by our biases or limited perspective. In contrast, a coach provides an external and experienced viewpoint. They see the nuances in our techniques, the small yet significant errors in our form, and the habits that hold us back.

I've grown more in my abilities over the last 3 weeks than I have in my first 6 months of playing tennis! 🚀

Here's how:

With a coach's guidance, our practice sessions become more targeted. They guide our focus, correct our mistakes in real-time, and introduce drills tailored to our needs.

This structured and deliberate approach ensures that we're not just practicing but practicing right. The result? A faster and more efficient improvement trajectory.

For anyone out there striving for excellence, be it in tennis, a professional field, or a personal hobby, remember this: While passion and persistence are crucial, the guidance of a mentor and the discipline of deliberate practice can be the difference between slow progression and accelerated mastery.

I'd love to know if you've ever taken advantage of deliberate practice to master a skill.

And stay tuned for more insights on my journey. The road to 4.5 continues! 🎾🔥

(Posted 10.7.23)

I have a crazy goal: to qualify for the Jewish Olympics.

Spoiler alert – I am currently terrible. I started playing this year and I need to get to a collegiate level of play to have any shot.

But here's the thing; I am embracing every flawed forehand, every misguided backhand, and every missed serve. Why? Because I believe that embracing my inadequacies is the first step towards mastery.

We live in a world that celebrates perfection, where social media highlights are filled with nothing but accomplishments.

But what you don't often see is the journey, the missteps, and the countless hours of practice that go into honing a skill.

Every professional was once a beginner. And in those early stages, they weren't pretty. They weren’t perfect. But they were resilient.

Being bad at something is a gift.

It provides us with a blank canvas, a world filled with endless possibilities. Each mistake is a lesson, each failure a stepping stone.

If we approach each setback with a learner’s mentality, we evolve. We grow. We inch closer to our goals.

So, why am I sharing this with you? Because I want you to enjoy my pain. Not in a sadistic way, but as a testament to growth, to vulnerability, and to the beauty of the journey.

Today, you might be chuckling at my missteps, but in the coming months, you’ll witness a transformation.

For weeks, I was stuck. In my journey to learn to play tennis and compete in the Jewish Olympics, I couldn't figure out a vital part of play.

My wrist just wouldn’t twist (pronate) right for a proper serve and volley, even with my amazing coach, Elliott, trying every trick in the book. 🎾❌ We were almost giving up and looking for a “Plan B” for those shots.

Then came a 4-day work trip with my kiddo! 🚗💼 His big wish? Play LOADS of pickleball. Now, ever since I started playing tennis, I've been a “Tennis Only, Please!” kind of gal. But I decided to say YES to any idea that he brought up on the trip, so pickleball it was! 🥒🏓

And, oh boy, did we play! Hour after hour, day after day. I thought I could make the most of it by working on my footwork and holding the paddle the way I would hold a tennis racquet. And guess what happened when I got back home?

During my next tennis lesson, BAM! I served and volleyed with the right grip, just like that! 🎾🔥 Elliott and I were both like 😱 because something clicked while playing pickleball and fixed my tennis problem!

🌟 Lesson of the Week: 🌟 Always be open to learning, even from unexpected places!

Who knew that saying YES to pickleball (and fun times with my son) would be the secret sauce to my tennis progress? 🚀 So here's a shoutout to being open, trying new things, and finding happy surprises along the way! 🎉❤️

🔗 For a full recap of my tennis journey, including how it got started, I've linked a recap post in the comments! 🎾🌟

#GrowthMindet#AlwaysBeLearning#TheInnovatorWithin

(This is my weekly series documenting my journey from being a tennis amateur to attempting to play in the Jewish Olympics - striving to get to a collegiate level of play)

Why do most people fall short of their goals? It's not because they lack talent, drive, or ambition. It's because they haven't prepared for setbacks. And setbacks are inevitable.

It's almost comical when you think about it. How often we set ourselves up for disappointment by failing to acknowledge that setbacks are a natural part of the journey. And not planning on what we'll do when they happen.

This week was one of those setback weeks for me.

I had every intention to stick to my training, to push myself harder and to refine my skills. But life had other plans. Between juggling the responsibilities of looking after two little ones while my husband was away, managing three client engagements, and my coach getting sick, there was simply no room for tennis.

And as I looked at my untouched gear (pictured here), the familiar voice of doubt started to creep in. "This is unrealistic. How will you ever find the time to achieve this? You're thinking too big this time. It's never going to happen."

But here's the good news. I've been down this road before. Every ambitious goal I've set for myself has been met with challenges, setbacks, and that nagging voice of doubt.

What's different this time? I'm prepared for it. I expect it. I've accepted that there will be days, or even weeks, where I feel like I'm moving backwards rather than forwards.

I just know that this setbacks isn't the end. It's simply a pause, a moments to reflect, and an opportunity to bounce back stronger.

So while this week was a dud, I'm not discouraged. I've scheduled my lesson for next week and am even working on scheduling my first match 😮.

Do you have any advice on bouncing back from setbacks? Anything you like to tell yourself or do?

(This is a series documenting my journey from being a tennis amateur to a collegiate level player in a year and a half and attempting to qualifying to play in the Jewish Olympics)

The last few weeks have been super frustrating.

I’m doing great in practice with my coach. He’s telling me that we’re progressing well. But anytime I play a competitive match, my nerves take over and I mentally sabotage myself.

I'm not even putting too much pressure on myself to win. I worry about embarrassing myself in front of the other players, which causes me to overcorrect and…embarrass myself in front of the other players 🤦🏻. I just don’t play as well in a match as I do in practice.

Even though this is my first time playing competitive sports, this feeling of self-sabotage is oddly familiar. For the first eight years as a keynote speaker, I would get physically ill before every speech. It seemed like my brain (which was very excited about the opportunity) and my body (which was trying to put a stop to it) were not on the same page. Thankfully, I’m on the other side of that challenge, but I would love to solve this tennis situation in less than eight years 🙃.

So, I'm on a quest. A quest to tame my game-time nerves.

I’m asking a lot of questions about what’s possible and trying out a lot of experiments.

Please send all the tips and tricks.

My big takeaway so far is that in this game of life, whether with a racket or a microphone, the real match is within.

This kind of strategic decision making is one of the top skills innovators must master.

Here's how I make the decision without letting my pride take over:

I'd like to add that one way I make this decision easy on myself, is I avoid it altogether by

employing a stage gate process for evaluating where I invest my time and resources.

The stage-gate process divides the development of a new initiative into stages separated by

gates. At each gate, the ongoing viability of the initiative is evaluated based on predetermined

criteria:

Our resources—whether time, talent, or capital—are finite, and successful innovators

understand that we have to continuously reassess to make sure that we don't get stuck.

They recognize that every excuse, no matter how valid it may seem, is a self-imposed roadblock

on the path to transformative change.

Rather than getting bogged down by challenges or setbacks, innovators harness them as

catalysts for creativity and adaptability. They maintain an unwavering belief in their vision for organizational growth and development, knowing that for every problem, there's a solution waiting to be discovered.

This relentless pursuit of betterment through an innovator's mindset, paired with a refusal to let excuses deter them, is what sets innovators apart and drives them towards groundbreaking achievements.

I've listed out the common excuses I've heard inside organizations, and how innovators can

combat them:

The new age of business demands an innovator mindset not only from a select few but from everyone.

Whether you're in the mailroom or the boardroom, innovation is the new standard operating

procedure. So, to all my friends across the organizational spectrum: It's time to step up, sideline

those excuses, and let your innovative spirit shine.

Innovation #NoMoreExcuses #OrganizationalGrowth

In my journey from a 2.5 to a 4.5 tennis player, I've learned a profound lesson that goes beyond

the boundaries of the tennis court: The immense value of deliberate practice.

It would be easy for me to spend hours on the court, hitting ball after ball, hoping to improve.

In fact, that's how I spent my spring and summer.

While time and effort are commendable, they alone aren't enough for substantial growth.

That's where the magic of deliberate practice comes in.

Deliberate practice is a concept that was popularized by Anders Ericsson, who studied the

habits of top performers across various fields. Ericsson's research showed that with the right

type and amount of practice, most people can achieve exceptional levels of skill and

performance in almost any organizational coaching domain.

But it only works if you follow this very specific kind of practice (I outline the steps at the end of

this post).

I had my first lesson with a coach about 3 weeks ago, and my body was so sore after that I kept

saying, "what have I been playing all this time???" My body was just not used to the

movements he was asking me to do!

That's my coach Elliott, in the picture.

When trying to improve on our own, we rely heavily on self-assessment, which can often be

clouded by our biases or limited perspective. In contrast, a coach provides an external and

experienced viewpoint. They see the nuances in our techniques, the small yet significant errors

in our form, and the habits that hold us back.

I've grown more in my abilities over the last 3 weeks than I have in my first 6 months of playing

tennis!

Here's how:

With a coach's guidance, our practice sessions become more targeted. They guide our focus,

correct our mistakes in real-time, and introduce drills tailored to our needs. This structured and deliberate approach to organizational coaching through leadership coaching services ensures that we're not just practicing but practicing right. The result? A faster and more efficient improvement trajectory.

For anyone out there striving for excellence, be it in tennis, a professional field, or a personal

hobby, remember this: While passion and persistence are crucial, the guidance of a mentor and

the discipline of deliberate practice can be the difference between slow progression and

accelerated mastery.

And if you want to know if you're taking advantage of deliberate practice, consider these

important elements:

In contrast, here are the potential issues with solo practice:

I'd love to know if you've ever taken advantage of deliberate practice through leadership coaching services to master a skill.

And stay tuned for more insights on my journey. The road to 4.5 continues!

When it comes to life's trajectory, most of us spotlight our wins. But what if we began viewing our growth through the lens of opportunities we consciously sidestepped? 🤔

In our hustle and bustle world, almost everyone has a résumé. It's that trusty document, detailing our proudest moments, like a passport stamping our professional journeys. But, what if there's another side to this story?

Enter: The Reverse Resume: the goal setting and professional development plan I use to test whether I'm being innovative enough as a professional.

The Balance of Choices

While a conventional resume lists our achievements, the Reverse Resume is the flip side; this goal setting and professional development plan captures all the opportunities, projects, and endeavors we’ve turned down.

And the driving force behind this concept? Growth.

The Yearly Review

Each year, I pull out my reverse resume, taking a moment to reflect upon the array of opportunities I’ve declined. And here’s the catch: I want this list to be more impressive with each passing year. If the opportunities I'm saying no to are amazing, it’s a clear indicator that the ones I’m saying yes to are of even greater value and alignment to my goals.

By turning down the good, I’m holding out for the great career growth opportunities.

The Strength in Saying "No"

So, the next time you're faced with the difficult decision of declining a good opportunity, don't wince in hesitation or regret. Instead, celebrate that addition to your reverse resume, for it's a testament to your evolving standards and unwavering vision.

The Reverse Resume isn't about reveling in missed chances but celebrating the growth that leads us to make better choices. Remember, as you evolve, so should your boundaries.

Be proud of what you decline, for it is a sign of what truly matters.

Embracing The Reverse Resume Approach

If you're intrigued by this concept, here's how you can start:

Concluding Thoughts

The Reverse Resume serves as the negative space of our lives, highlighting the paths we consciously choose not to tread. This goal setting and professional development plan is a celebration of discernment, alignment, and growth. While the world might laud us for our achievements, let's also take pride in the opportunities we've declined.

After all, they are the clearest indicators of what truly matters to us.

Have you experienced any reverse resume moments lately? Reflect upon them, for they are the signposts guiding you towards an even more purposeful journey.

While growth only occurs in a state of curiosity, it's equally important to acknowledge that it's not effortless to get into a state of curiosity through the fixed mindset and a growth mindset.

In fact, if we aren't mindful about it, we can find ourselves in various states that inhibit growth:

1. Apathy or Complacency: Apathy or complacency is a state characterized by a lack of interest, enthusiasm, or motivation. In this state, we become indifferent or resigned to our circumstances, leading to a diminished drive for growth.

Apathy can result from feeling stuck, disengaged, or overwhelmed, and it can impede progress by hindering the desire to explore new ideas, seek opportunities, or invest in personal development.

2. Fear and Resistance: Fear and resistance arise when we are hesitant to step outside of our comfort zones or take risks. These states often stem from a fear of failure, rejection, or the unknown.

When we are consumed by fear and resistance, we may avoid challenges, new experiences, or opportunities that could lead to growth. Instead, we remain confined within familiar boundaries, limiting our potential for advancement.

3. Fixed Mindset: A fixed mindset refers to the belief that abilities and qualities are fixed traits that cannot be significantly developed or changed. Those with a fixed mindset tend to avoid challenges, ignore constructive feedback, and view setbacks as personal failures.

This state can hinder growth by stifling the curiosity and openness necessary for embracing new ideas, acquiring new skills, and persisting through obstacles by exploring a fixed mindset and a growth mindset.

4. Overconfidence or Expertise: While confidence is essential for growth, excessive overconfidence or feeling like the expert can hinder progress. When we believe that we have all the answers or that we have reached the pinnacle of our abilities, we become resistant to feedback, new perspectives, and opportunities for growth.

This state can lead to complacency and a reluctance to learn from others or challenge our assumptions, limiting our potential for further development.

5. Distractions and Busyness: In today's fast-paced world, we can easily become consumed by distractions and busyness. Constantly focusing on mundane tasks or superficial activities without making space for introspection or deep engagement can impede growth.

This state can prevent us from allocating time and energy to pursue meaningful learning experiences, reflect on our progress, or invest in intentional personal and professional development.

_____________________

While these alternative states of a fixed mindset and a growth mindset may hinder growth, it's important to recognize that they are not permanent conditions.

As a business growth keynote speaker, Diana Kander helps cultivate self-awareness, embracing curiosity, and actively working towards a growth mindset, we can shift away from these limiting states and create an environment conducive to continuous growth and development.

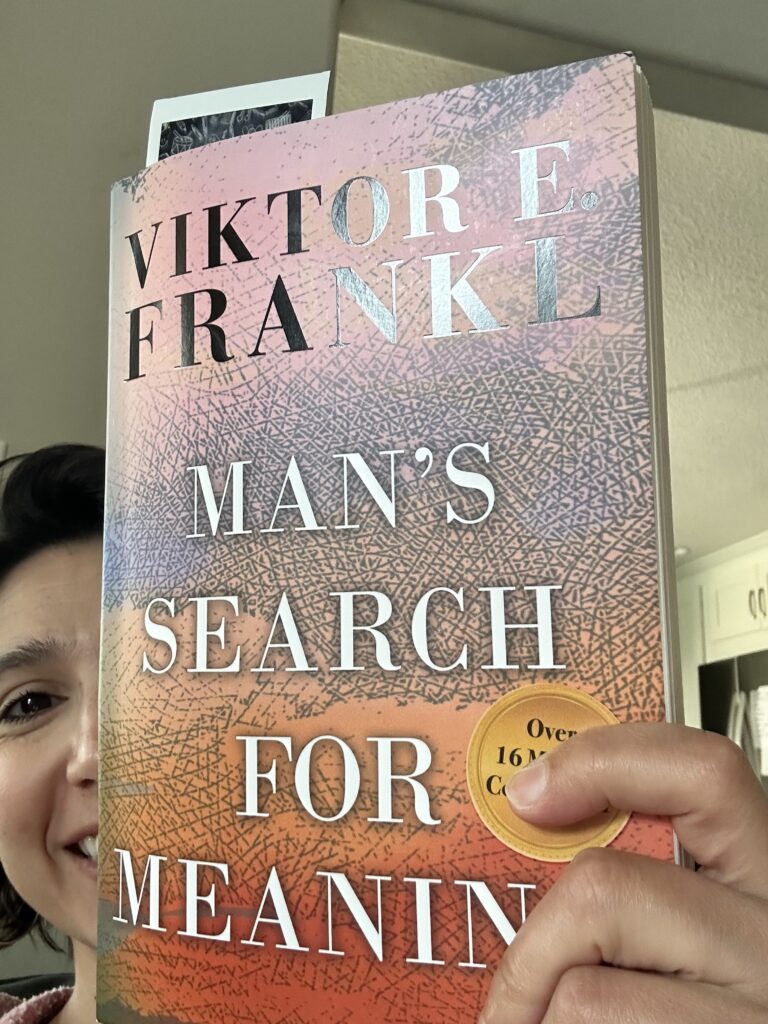

The Big Idea:

It's the story of one man's experience in 4 different concentration camps over 3 years. He details the brutal, unimaginable treatment that he endured, the loss of everyone he loved, and how, through all of that, he didn't lose meaning in his life. A practicing psychiatrist both before and after the war, he explains that having meaning, much more than striving for pleasure or power, will help you get through life's challenges and allow you to be happy.

Background:

In 1942, just nine months after his marriage, Frankl and his family were sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. His father died there of starvation and pneumonia. In 1944, Frankl and the surviving members of his family were transported to Auschwitz, where his mother and brother were murdered in the gas chambers. His wife died later of typhus in Bergen-Belsen. Frankl spent three years in four concentration camps.

While head of the Neurological Department at the general Polyclinic Hospital, Frankl wrote Man’s Search for Meaning over a nine-day period. The book, originally titled A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp, was released in German in 1946. The English translation of Man's Search for Meaning was published in 1959, and became an international bestseller.

The book is 50% his account of surviving in the camps and 50% his theory of Logotherapy that he believes is a better psychiatric approach to dealing with neuroses like anxiety and depression.

Top 10 Takeaways:

Rating:

Final Thought:

I am so moved after reading this book that I don't want it to leave my side. Like I literally want to carry it around in my backpack wherever I go.

I just never want to forget how I felt reading it. The thoughts of what we as humans a capable of doing to others and at the same time what we are able to survive while maintaining our humanity.

And I didn't mention it above, but I don't want to forget the story of Dr. J – You can never predict the future actions of a man. People can change in radical ways.

Other quotes I loved:

I set a goal to do the splits this year.

I've never done the splits. I'm not even close. Here's my laughable starting photo.

And yet the goal doesn't really matter.

What matters is my mental model of how I, Diana, learn to do new things. Sometimes impossible seeming things. And my real goal is to learn the flaws in this model and update it using the splits as my vehicle.

Setting and achieving your goals are nothing more than wishes.

And even if you have a plan for accomplishing your goal, that's not as strong as having a mental model for how you as a person generally achieve goals.

This Goals Achievement Mental Model would include answers to the following questions:

My goal is not just to achieve new things each year, it's to refine my philosophy about how I achieve things. Tweaking my mental model each year gives me a clear roadmap to follow, making it easier to stay on track and avoid getting sidetracked or discouraged. And it helps me spend my time better. I'm dedicating 15 minutes a day to doing the splits. That's a very big return on a minimal output.

So, while the setting and achieving your goal itself may be important, your personal methodology of how you accomplish goals or resolutions is a lot more valuable to your long term growth. If you can upgrade your mental model for achieving goals each year, you'll find that your growth becomes exponential.

Don't get me wrong, I do want to hear about your New Year's Resolutions! It's fun to go for big things! It's just that the goal itself doesn't interest me nearly as much as your mental model to get there.

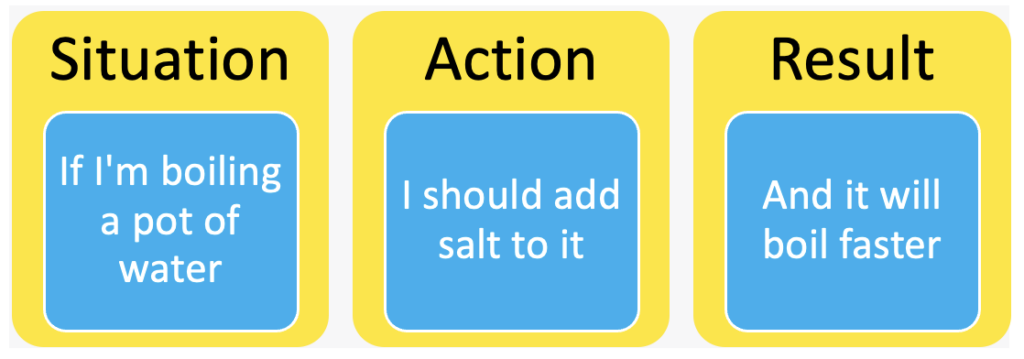

Many of our daily actions are habitual, meaning they are performed automatically and without conscious thought. It's a useful way for us to save mental energy and streamline tasks that are performed frequently.

These automatic actions are often based on our learning mental models, which are the assumptions, beliefs, and frameworks that we use to make sense of the world around us. They are like little formulas about how we believe things are supposed to work.

Here's a simple example:

Except this mental model is actually incorrect. Salt doesn't make your water boil any faster (unless your pot is filled with 20% salt). If you want your water to boil faster, it would be smarter to just start with hot water.

And we have tens of thousands of these theories, big and small, secretly governing many of our actions. Here are just some of the categories they fall into:

But we haven't spent much time articulating exactly what our philosophies are in these areas. We're just mindlessly acting based on these hidden rules, instead of using a strategic mindset.

When I was in high school, one of my health learned mental models (thanks to some brilliant commercials) was that the key to being physically fit was drinking as much milk as possible. Do you remember those, "Milk, It Does a Body Good" commercials? They were very effective.

And when I didn't make the team because I was frothing at the mouth during tryouts (this is what happens when you drink nothing but milk for two days and then engage in aerobic activity!), I didn't question the mental model. I blamed the coaches for having too much running and not enough shooting drills during tryouts. I also declared that I just wasn't a runner. But I held onto that milk philosophy for a decade until I started proactively learning about health and fitness.

We protect these assumptions by never questioning them. Where did they come from? Are they working for us? Do they need updating?

And yet learning mental models determine how strategic we are in our actions. If our philosophies are accurate and helpful, they can guide us toward big wins. On the other hand, if our mental models are flawed or limited, they can lead us down the wrong path and prevent us from achieving our goals.

Or, in the words of Charlie Munger, "You get further in life by avoiding repeated stupidity than you do by striving for maximum intelligence."

Method 1: Updating our questions

1. When you ask a question that you ask often, reflect on whether you’re getting the kind of response that you’re hoping for.

Ex: You ask your kid after school how their day was. They say "Fine." You try again. You ask them, "What was the best part?" or "What did they learn?" They don't remember. It feels like a very unsuccessful interrogation. These questions and learning mental models that make you think they should be working aren't serving you.

2. Try some other questions instead to see if you get a better response. Ask others about what questions they use to accomplish the same goals.

One question that has worked well for me is: "How was your day on a scale of 1 to 10?"

Method 2. Mental Model reflection

1. Identify an area of your life that you would like to grow or improve. (It's not too late for New Year's resolutions!)

2. Make a list of all the mental models you currently have about that subject and see which ones might need to be updated or might not be serving you.

3. Seek out new perspectives on these philosophies. Consider asking for feedback from others.

4. Update one mental model at a time and come up with a way to test the new approach.

Method 3. Inspiration

1. Find a source of inspiration that regularly challenges your existing learned mental models. My monthly newsletter attempts to do just that. Ask This Not That is a monthly dose of question makeover – in which I take one common question and offering an alternative that could help you get much better results.

2. Join a group of people who like to talk about this topic. There are strategic mindset groups on both LinkedIn and Facebook.

Whatever method you choose, understand that the quality of your strategic thinking is determined by the life philosophies swimming around in your head. Identifying and upgrading these mental models can help you make better decisions, solve problems faster, and identify big opportunities.

To beat the overconfidence effect in yourself and others you need to argue like you're right but listen like you're wrong.

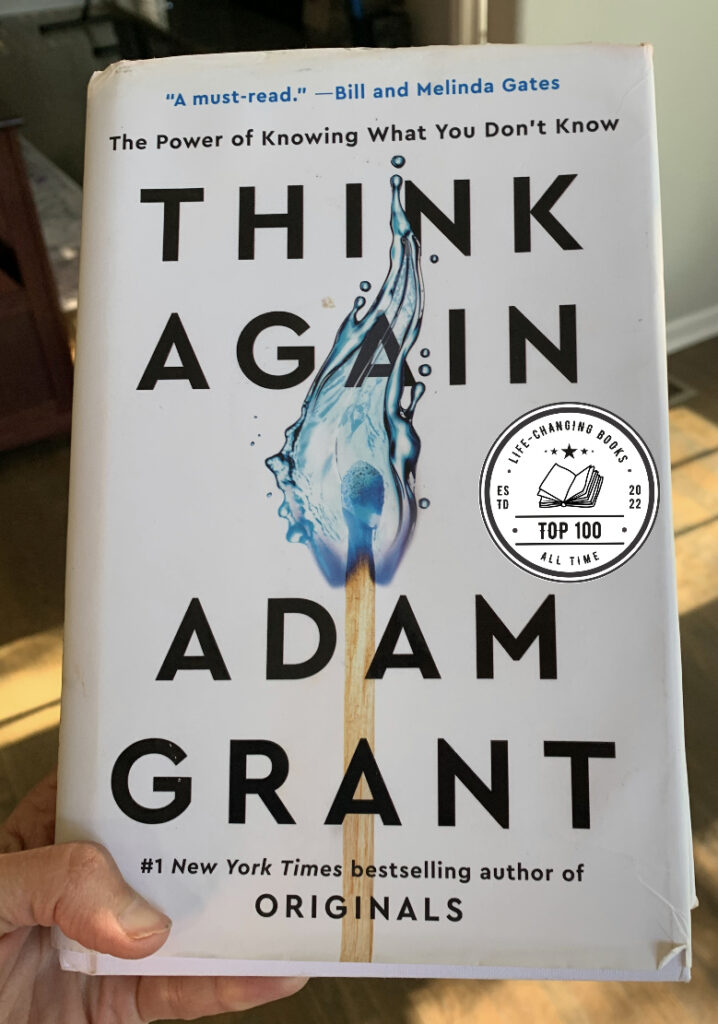

Adam Grant was the youngest tenured professor at Wharton School, receiving tenure at the age of 28. He specializes in organizational psychology. He has been Wharton's top-rated professor for seven straight years.

He's authored four New York Times Bestselling books. Think Again is his latest work, published in 2021. It has 12,000 customer reviews on Amazon, averaging 4.6/5.

Fun fact: Grant was named an All-American springboard diver in 1999 and he worked as a professional magician during college.

I don't know of another business book that more people have owned but not read. Which is ironic. I was one of those people. My neighbor Becky kept telling me how much it aligned with my curiosity work, and in my head I was like, "Yea, yea, I teach this stuff, what could I possibly learn?" And the answer is quite a lot.

This book should be required reading for every senior leader. And it would be of significant value to parents, teachers, politicians, and those of us who don't want to stop growing and improving ourselves.

For the past 60 years the financial services industry has been booming. Since 1980, year over year growth rates tripled and large entities flourished as smaller competitors crumbled. With low interest rates and new regulations, banks grew quickly as the rest of the marketplace piggybacked off their success. Savvy and risk-averse business men and women flocked to the industry; a career in financial services seemed like a safe bet.

Such a prolonged period of success is both a blessing and a curse. What made the financial services sector soar has also been responsible for nearly crippling it and taking our economy with it.

By succeeding for so many years – practically a lifetime in the business world – financial service firms remained virtually untouched while other industries were being disrupted. This made them dangerously comfortable. The strategies that once promoted growth stopped working in the same ways in today’s hyper competitive economy.

As an innovation keynote speaker, I understand how ignoring changing tech and forgoing innovation experts for “guaranteed profits,” created the ideal environment for disruption.

In stark contrast to large, collateral backed loans, today’s financial innovators focus on small and specialized services like micro-loans, peer to peer lending, and small business lines of credit. The walls that once separated consumers from their finances gave way as startups like Square, Stripe, Coin, and Dwalla eliminate fees while providing new value.

Even business we typically wouldn’t consider part of financial services got into the game and expanded the field of competitors. Home Depot now offers loans for home remodeling projects. Starbucks and Chik-Fil-A created an app to speed-up payments and create financial loyalty. Walmart, Google, Apple Pay, Paypal are now viable forms of currency. The threats are ever increasing, and the financial services industry isn’t prepared to innovate and adapt.

While it's not fair to blame success for the impending doom, it is important to address the traps of reaching expert status. Yes, being really good at something, being an expert, can be what stifles innovation.

Enter: The Expert Traps. The silent and unseen killers of creativity and creation. When we feel like experts at what we do, the following traps await us:

Trap #1: We Stop Trying to Learn and Improve

Confidence in your skills is important. We’d all like our bankers, lawyers, and employers to be good at what they do. It’s a valid and honorable trait. However, when confidence grows without limits and exceeds its true skill, we lose the incentive to improve.

And this is what suffocated innovation experts in the financial industry. Big banks and firms were killing it (as in, they were raking in the profits). They were the best of the best; taking the time to reassess their offering would have only distracted them from continuing to win. Or so they thought.

As an innovation keynote speaker, I understand how this dangerous confidence convinces experts that it isn’t necessary to test and question the status quo. Hubris whispers “You know what you’re doing. You’ve got the track record to prove it.” While the beginner or the novice looks for opportunities to improve, the expert believes they will always be the best of the best, even as their stock prices plummet. This is one of the reasons they never saw the 2008 collapse coming.

Trap #2: We Don’t Examine Our Successes

Looking backward is a no-brainer when we lose. We can learn from our mistakes. Being a loser incentivizes us to examine what went wrong. But when we win, the opposite happens. Why look back when the future's so bright? By assuming the win was a result of perfect strategy and execution, you could ignore big opportunities to improve.

Winning is awesome. You will never find me happy with a loss. However, constant improvement and innovation experts demand we approach both losses and successes as a beginner. And a beginner never stops reflecting. If a beginner receives unexpected praise from a superior, the novice will ask, “What did I do and how can I do it again?”

So hold your head up high. Things are going well! Now turn around and take a hard look at how you got there. Can you repeat it? Was it luck? And most importantly, what could you have done better? Ask the hard questions and live to succeed another day.

Trap #3: We Play it Safe

Ah, to be the best of the best. It feels great to be at the top. So great, in fact, you’d rather not look down. Falling from such heights could be deadly.

For many in the financial industry, reaching the top triggered the instinct to survive. How can we avoid falling? What can we do to stay absolutely still and not compromise our position? Delaying or completely avoiding action feels like the safer option when you’ve fought so hard to get there.

But a beginner has nothing to lose. The beginner defaults to action, to responsible experimentation and seeing what happens. For the beginner, the opportunity to learn something new is more motivating than potentially making a mess. Failure is inevitable for a beginner, so why not try?

This doesn’t mean beginners experiment with reckless abandon, the goal is success after all. Beginners forgo guaranteed success in favor of growing their abilities. Innovation experts hunker down and hold their position, even if it means ignoring an oncoming catastrophe.

Understanding the traps is a great first step. But it’s not enough. Research on cognitive biases shows that being aware of biases/expert traps doesn't do much to reduce their effects. All of the above traps happen subconsciously. Trying to “watch out” for the traps is just as difficult as “watching out” for how you’re breathing while you sleep.

The only way to control for the traps of success and expertise is to implement guardrails to keep your work on the right path. Here’s what I suggest:

1. Look for Negative Evidence

When you’re making a decision or choosing a strategic direction, assign someone to challenge your bias for a particular direction. The military calls them red teams, some in business call them a devil's advocate, and I call them provocateurs. Either way, find an individual or team of outsiders who have no vested interest in your project. They care enough to help, but not enough that they will be affected by the outcome. These innovation experts are in the best position to open your eyes to blind spots.

2. Retrospectives to Examine Success and Failure

Schedule a meeting at least once a year to look back at your project or company and examine the processes and results. Retrospectives create a structure for reflection, learning, and planning. No matter how well things are going, A Retrospective shows you how to correct glaring strategic mistakes that are invisible when you’re executing on day-to-day activities. I’ve used this process countless times and if you’re not sure where to start, you can use my 20+ page guide to running a successful Retrospective here.

3. Experiment

The most innovative companies are only so because of constant experiments. Experiments to see if they can improve things that are already working well. Experiment to find solutions to pervasive problems. Experimentation increases the velocity of decision making. It helps kill or change projects that aren’t working and lowers the cost of finding solutions. The best experiments use the scientific method, and if you’re not sure how to set up your next test, check out my innovation keynote speaker template here.

Complacency is the enemy of innovation experts. The more comfortable you are, the less you work to improve and create new value. And complacency always takes its toll. As the pace picks up, the expert falls behind. Only those focussed on constant growth and improvement, even in good times, will be the ones to achieve sustained success.

Adopt the mindset of a beginner, build your retrospective strategy, and never stop fighting to improve. If you never settle, you will never peak! Let’s make the financial services industry boom for another 60, shall we?

(Note: This is the second installment of a multipart series on conducting customer interviews and discovering true migraine problems. And check out the first article in the series.)

Ok, you’re on the bandwagon. You understand that you need to a get to a new level when it comes to understanding your customers and finding their migraine problems. You need to understand them better than they know themselves.

Here’s the thing: When you go out to interview customers, they are probably going to LIE to you.

I’ve lost count of how many companies I’ve seen fail while insisting that everyone they’ve talked to loved their idea. They think they’ve conducted the customer interviews they needed, but they didn’t understand one of the most important rules to customer interviews:

People’s natural inclination is to lie during interviews

Think about the last time a friend told you about their “brilliant” new idea that you thought was really dumb. Were you 100 percent honest with your friend? I bet you weren’t. You, and most people, would probably lie a little bit to get out of the awkward situation. It’s a lot like that for your customers. Their natural inclination is not to be completely honest with you during an interview. They want to figure out the answer you’re looking for and give you that answer so they can leave the conversation as soon as possible. Customers don’t lie to be malicious; it’s just the opposite.

They can clearly see how passionate you are about an idea, and they don’t want to be the one person to hurt your feelings.

When I was pregnant with my son and trying to decide on names, I conducted a fun experiment. I wanted to see what people really thought of the names my husband and I were considering, so when someone asked me what I was naming my son, I would give one of two responses. To one group, I said I wasn’t really sure, but I liked names like Branch, Major and True. To the other group I would say I was naming my son True, and that I was really excited about it. I quickly found that the two groups reacted very differently to my responses. When I told people I was still deciding, more than 90 percent would tell me they didn’t like any of the names I had picked. But when I acted excited about one name, over 90 percent of people told me they loved the name True and would go on and on about how unique it was. Obviously I wasn’t hearing the truth from everyone.

With my son’s name, I was just conducting an experiment. I didn’t really care what people thought. But, when you’re talking about starting a company, hearing the truth from customers is vital to your success. The problem is, if they can sense the answer you are hoping for, they will jump to give it to you.

The key to understanding your customers real pain and current ways of solving existing problems is to get them talking. You want to ask them open-ended questions that will elicit a lot more valuable details than the response to the specific question. (More on open ended questions coming soon – make sure you are subscribed to get the article)

Now, think about the last time you got a call from a telemarketer trying to solicit a donation or get you to respond to a survey. I bet with every question they asked, you went through a mental Rolodex of responses that might make the call end as soon as possible. You weren’t thinking of the real answers to their questions, let alone additional information they might find useful. You were feeling uncomfortable and willing to say anything just to get it to end.

Most customer interviews are the same. If you don’t do a good job of getting them comfortable and engaged before starting to ask them questions, they will just be looking for the fastest way to exit the conversation, and usually that means saying something like “That sounds awesome, I would probably buy that.” They know that if they disagree with anything you said that you’ll want to argue with them, so they know that by agreeing with you and telling you how great your idea is, you’ll have no option but to end the conversation and go finish building your new product.

Many times when you present your idea, you’ll outline all the different ways it can benefit their lives, putting your potential customer in a situation where they look dumb if they disagree with you. For instance, you can tell them all of the money they are wasting each year from poor insulation in their home and all the benefits your product could provide to solve it for them. What could they say? “I don’t really care about all that money I’m wasting.” Or “I don’t really care about the environment.” Instead, they would likely try to save face by telling you how interesting it sounds and how they will think about buying your product. They aren’t going to. They just don’t want to look dumb, uncaring, or uninformed.

Once you know that your customers are inclined to lie to you, your whole strategy should change. Your objective should be to trick them into telling you the truth, and to make it hard for them to lie by keeping them in the dark about what you’re really after. It’s the difference between asking someone’s opinion on a few ideas you’re considering and asking their opinion on one idea in which you obviously have a vested interest.

Interviewing customers is one of the most difficult steps in the entrepreneurial process. It’s not as exciting as launching a website or raising money. The truth can hurt too, especially if customers don’t end up liking your big idea. But, the only thing worse than not talking to customers is talking to customers who you don’t realize are lying to you.

No innovator fails because they couldn’t build their product. They fail because no one found value in what they built.

Here’s what usually happens when someone gets a new idea:

Sadly, this is the typical cycle of innovation. Most new initiatives fail.

But successful innovators know that they have a very powerful tool at their disposal to significantly decrease the risk of innovation: experimentation.

Experiments are small bets that you make to see if what you believe to be true is actually true - to see if your predictions about the customer and the market are right. It’s something small that you do today to prove that you are spending time and money on the right things . . . on building something that people will buy.

In All in Startup, the reader meets Owen after he has followed the very process outlined above and wasted hundreds of thousands of dollars and a year of his life building something that wasn’t meeting any of his projections. What could he have done before he committed his available resources to executing his plan, to make sure customers would be waiting for him when the product was ready? He should have run some experiments!

But the hardest thing about experiments is running them correctly.

Here are some guidelines about what a good experiment looks like.

To run a good experiment, you need to determine and document these five elements before you begin:

What is it that you’re trying to learn? Or what are you trying to prove? What are the riskiest assumptions you’ve made about your idea? For Owen, his riskiest assumption was that people would buy half-priced, used bicycles online.

Your high school science classes taught you what you need to know for this part. This is a statement that you’re trying to prove true or false through the experiment. The result will be a “yes” or a “no” so you need to phrase your hypothesis appropriately.

For example, a good hypothesis would be based on this setup: “If I do this action, then this outcome will happen.”

The key is to make sure that your Hypothesis helps you get closer to the Goal you outlined above and reduce the risk of your riskiest assumption. The hypothesis can help you test whether you have identified the right customer segment, whether your target customers actually have the pain point you think they do, whether they perceive enough value in your solution to buy it, whether your solution actually solves their pain point, whether you’ve identified the right channels to target your customers, whether your supplier cost estimates are accurate, whether you’ve chosen the right price point for your product, etc.

The biggest mistakes in putting together a hypothesis include:

Some example hypotheses Owen could have created:

Who are you targeting with the experiment? How are you filtering who will participate and who won't? For instance, if Owen puts up a landing page to see if people interested in road bikes will want to buy his bikes, what kind of information is he gathering on the landing page to make sure that the right people are seeing his messaging before he decides whether it's working or not?

Tip: If you are having trouble limiting your target subject for the experiment, try first listing out people who wouldn't fit into your target subject. I.e., for Owen it's people who want to buy a $100 bicycle at Walmart or Target or perhaps people who are interested in roadbikes but have never actually purchased one because they think they are too expensive.

How are you going to conduct your experiment? What’s the time period? How do we know when the experiment has started and has finished? How many people will you target? Who will carry out the experiment?

A key question to ask yourself here is: is this the least amount of time and effort I can spend to test this hypothesis? Remember, this is supposed to be a small bet you can afford to lose. Too many people think their experiment is building a lighter version of the final product – taking 6 months to put together.

You should be able to run your experiment in under 2 weeks. I will frequently push my innovators to come up with a hypothesis and figure out a way to start the experiment within 24 hours.

Something of value that the subjects of your experiment have to give you in order to prove whether your hypothesis is true.

The key is that it be something painful for them to give up in order to demonstrate their sincerity. This can include anything from money to time to a commitment of certain resources. Basically anything that demonstrates customers will be willing to part with something they value in order to obtain the product or service you’re offering. You want to make sure that they aren’t just trying to be nice to you or lying about their intent for some other reason.

When you are trying to de-risk an idea, the worst kind of evidence you could gather is a false positive (i.e., perceived interest from people who don’t actually see value in your product) because it gets you excited about moving forward and going All In on the idea. Simulate a world where your product already exists, and see if your customers will give you the currency you think you deserve.

In the Owen hypothesis examples above, Owen is asking for specific actions, a commitment of money or commitment of time to demonstrate whether he’s identified the right customer segments, marketing channels and distribution channels.

Before you begin your experiment, it’s important to define what success and failure will look like. If success is having 25 percent of customers give you currency, what does it mean when only 15 percent provide it? Has your experiment failed?

You need to set up these parameters before you begin the experiment, so that you’ll objectively understand the outcome and not be forced to debate what the results mean with your team.

Additionally, a friend of mine, Justin Wilcox, suggests that innovators write out two separate plans of action to pursue depending on whether the experiment reveals the hypothesis to be correct or incorrect. He emphasizes that this should be done before conducting the experiment. Some people have such a hard time deciding what to do if an experiment doesn’t go as they had planned that they end up making up a justification of why it was a success and allowing themselves to keep moving forward on their idea.

OK. Those are the elements you need to determine and document before you begin your experiment. And while this experiment framework can seem cumbersome, remember, it is your single greatest asset in reducing the risk that goes with creating something new.

Corporate innovation is all the rage these days. With plenty of money and time at their disposal, employees have ample resources to create the next big thing. But before they commit too many resources to an idea, these intrapreneurs can learn a lot from successful entrepreneurs who operate with fewer resources.

Innovation within a corporation comes down to two factors:

Do you remember the Segway? The Segway is a two-wheeled, battery-powered machine that makes even the most popular kid in school look like he sits alone at lunch. What I’m saying is you look dorky riding the thing. There’s something about you not putting in much effort while standing and gliding down the street that just makes people uncomfortable.

When the Segway first came out, it garnered lots of attention. Steve Jobs predicted the Segway would be bigger than the PC. John Doerr, a prominent venture capitalist who backed Netscape and Amazon, said it would be bigger than the Internet. With this level of hype, the company raised more than $90 million. But it’s grand unveiling was a huge disappointment. It took the company its entire first year in business to sell the number of Segways it predicted it would sell every two weeks.

The company had generated a solution-based idea. The Segway was a shiny, new technological advancement…that nobody wanted. The product didn’t solve a problem for the customer. Most companies that are unhappy with the results of their innovation programs are generating these same kinds of solution-based ideas. They start with a technological advancement or a brain storming session that produce a product, and then they try to figure out who might want it.

They’re so excited to have created something new that they forget that no one necessarily asked them to create it in the first place. They just assume that if they build it, the customers will come. Unfortunately, that seldom happens. What innovative employees – or intrapreneurs – do differently is come up with solutions inspired by their customers’ problems.

Instead of taking stabs in the dark and guessing what people might like, why not go directly to your customer and figure out for sure? When Paul Buchheit at Google created Gmail, he did just that. He came up with a problem-based idea. Instead of modeling his email platform after others on the market (looking at competitors to see what features and benefits to include), Paul listed out all the problems he thought the existing solutions created for users. The existing email platforms had limited storage space, were hard to search through and were slow to load data. By designing Gmail around these problems, Paul created something that generated a lot of value to email users. He initially designed the gmail platform for his own use, but when others in the company saw it, they begged him to let them have access to the functionality he created. And when Gmail became public, users flocked to the service because word of mouth marketing was so powerful at explaining its value.

Word of mouth marketing only works when people feel compelled to spread the word – and that compulsion is borne out of feeling that a product has solved a tangible problem. Gmail wasn’t just different to be different. It was different in a way that generated a lot of value for its customers. So much value that they wanted to tell people about it at school or work.

1. How employees generate ideas (problem-oriented vs. solution-oriented ideas)

Do you remember the Segway? The Segway is a two-wheeled, battery-powered machine that makes even the most popular kid in school look like he sits alone at lunch. What I’m saying is you look dorky riding the thing. There’s something about you not putting in much effort while standing and gliding down the street that just makes people uncomfortable.

When the Segway first came out, it garnered lots of attention. Steve Jobs predicted the Segway would be bigger than the PC. John Doerr, a prominent venture capitalist who backed Netscape and Amazon, said it would be bigger than the Internet. With this level of hype, the company raised more than $90 million. But it’s grand unveiling was a huge disappointment. It took the company its entire first year in business to sell the number of Segways it predicted it would sell every two weeks.

The company had generated a solution-based idea. The Segway was a shiny, new technological advancement…that nobody wanted. The product didn’t solve a problem for the customer. Most companies that are unhappy with the results of their innovation programs are generating these same kinds of solution-based ideas. They start with a technological advancement or a brain storming session that produce a product, and then they try to figure out who might want it.

They’re so excited to have created something new that they forget that no one necessarily asked them to create it in the first place. They just assume that if they build it, the customers will come. Unfortunately, that seldom happens. What innovative employees – or intrapreneurs – do differently is come up with solutions inspired by their customers’ problems.

Instead of taking stabs in the dark and guessing what people might like, why not go directly to your customer and figure out for sure? When Paul Buchheit at Google created Gmail, he did just that. He came up with a problem-based idea. Instead of modeling his email platform after others on the market (looking at competitors to see what features and benefits to include), Paul listed out all the problems he thought the existing solutions created for users. The existing email platforms had limited storage space, were hard to search through and were slow to load data. By designing Gmail around these problems, Paul created something that generated a lot of value to email users. He initially designed the gmail platform for his own use, but when others in the company saw it, they begged him to let them have access to the functionality he created. And when Gmail became public, users flocked to the service because word of mouth marketing was so powerful at explaining its value.

Word of mouth marketing only works when people feel compelled to spread the word – and that compulsion is borne out of feeling that a product has solved a tangible problem. Gmail wasn’t just different to be different. It was different in a way that generated a lot of value for its customers. So much value that they wanted to tell people about it at school or work.

Like Gmail, most successful products are built to solve problems. These problem-based ideas can only be found through customer interaction. You know you have a potentially great idea when you identify a group of customers who are ready, willing and accessible. Ready customers have identified a problem and are interested in fixing it, willing customers have taken steps to fix the problem in the past and have a budget to address the problem, and accessible customers are people you can easily reach. When you seek out this trifecta of customer interest for a problem-based idea, your product will practically sell itself.

Webvan is one of the most famous examples of a seemingly good idea that flopped. In 1996, Webvan launched an online grocery delivery business on the theory that people would pay money to avoid the hassle of grocery stores. Webvan spent hundreds of millions of dollarsbuilding an infrastructure (warehouses, technology, sales/marketing) based on a business plan that should have worked. But it never took off, and eventually the company went bankrupt in 2001. The online news site CNET went on to name Webvan the worst dot-com failure in history.

The Webvan story follows a plan-based approach to business that is commonly taught in business school. You write a business plan, see whether the numbers add up, and predict the success of a business based on this creative writing exercise. The plan-based approach seldom works because innovation is iterative. Your first business plan won’t be perfect, but most people don’t give themselves enough resources to make necessary pivots. Instead, many companies spend all their money to build a perfect product that is often a failure.

Entrepreneurs with the most positive results, however, know their company will be a success before their product ever hits the shelves. Instead of trying to predict the future, these entrepreneurs try to play detective by using an evidence-based approach to innovation. Theevidence-based approach determines customer demand and value of a product through experiments with actual customers. Simply by using this approach, the creators of Webvan could have launched a successful company or, at worst, abandoned the idea and saved hundreds of millions of dollars.

Zappos, an online shoe retailer founded in 1999, is the opposite of Webvan. Before the company spent a dime on building its infrastructure, it made sure it had customers by verifying a willingness among customers to buy shoes online. In the beginning, founder Nick Swinmurn would take pictures of the shoes available at local stores and post them on Zappos’s website. After a customer made a purchase online, Nick would return to the local store, buy the pair of shoes at full price and ship the shoes out manually. Before Zappos had built a single shipping warehouse, it was able to prove that its business model would work. This evidence-based approach is what prevented Zappos from becoming Webvan.

A few years after Webvan closed its doors, Zappos was acquired by Amazon for $1.2Billion. Swinmurn’s early experiments, while time consuming, obviously paid off. It’s important to verify that customers will actually pay for your product. A customer can easily give you an email address or a verbal agreement to buy your product, but real “currency” is different. When a customer gives you something that pains them, like money, time or an endorsement, you have strong evidence that your product is highly valued.

With everything on the line, entrepreneurs with access to little capital are under heightened pressure to build a moneymaking product on the first try. The best entrepreneurs reduce risk and expense by generating ideas that solve a problem and verifying those ideas with customer-backed evidence. This approach is often used out of necessity by entrepreneurs, but successful employee-driven innovations result from mimicking this method within the corporate environment. A problem-based idea and evidence-based approach is essential for innovation anywhere. Whether you have one employee or 5,000, the pain of innovation can be both eased and energized by following the example of successful entrepreneurs.

Launching new products and services is the only way to stay competitive in the new economy. Unfortunately, most companies have a process in place that stifles innovation.

I recently gave a TEDx talk titled "Our Approach to Innovation is Dead Wrong" about why our traditional thinking with regard to launching new products or initiatives is actually killing those new ideas before they ever have a chance to succeed.

What's working well and what do you think isn't working?

Looking forward to your thoughts.

A few weeks ago, at the National Association of Community College Entrepreneurship (NACCE) Conference, I took part in a panel discussion on the subject of preparing our future workforce for entrepreneurial thinking.

As companies increasingly express an interest in creative, innovative employees, one of the hottest questions in entrepreneurship education has become, “How do we prepare graduates to solve real problems and find opportunities for their employer rather than just show up to a job?”

The first question I received on the panel was “how are we doing as a community of entrepreneurship educators in preparing this future workforce?”

I was quiet for a few seconds. Frankly, I was nervous about what would happen if I said the first thing that came to my mind. I prepared myself to get booed off the stage and said, “I think we’re doing a terrible job. In fact, I think that we are actually killing innovative and entrepreneurial thinking through the classes that we teach.”

They didn’t erupt in boos. They let me continue.

In many entrepreneurship classrooms, professors make judgment calls about good ideas and bad ideas. Sometimes students pitch their ideas in business plan competitions to panels of experts that decide the value of a potential company. In the real world, logic and expertise can’t predict customer behavior. Even the top professional startup investors are wrong about predicting which startups will be successful 90% of the time. The only way to create a successful company is to discover what customers actually want through direct interactions, not assumptions. Instead of making judgments, we should push students to interact with potential customers and conduct experiments to see if they can simulate sales. If a student is required to appease an internal source of authority, like a professor, for the sake of their grade, then they won’t learn to respect the true source of authority, the customer.

Creating a successful company is not as simple as checking things off a to-do list. Yet many professors still give students a list of tasks—create a business plan, interview an entrepreneur, read a book—as if there is an easy roadmap to building a million dollar company. Entrepreneurship is an emotional roller coaster. It’s scary and exciting all at the same time, and, above all else, it’s fraught with uncertainty. If teachers aren’t giving students butterflies in their stomachs – making them feel overwhelmed or uncomfortable – then they aren’t preparing students for the challenges of entrepreneurship. And they certainly aren’t teaching them to develop entrepreneurial thinking. Instead, teachers who don’t push students out of their comfort zone are simply reinforcing traditional 9 to 5 employee thinking. There’s nothing wrong with a 9 to 5 employee, but it’s not the mindset companies are currently looking for as they interview business school graduates.

If you want to give your students real butterflies, then give them an objective and ask them to figure out how to achieve it. Better yet, send them out on some real experiential activities, like the activities suggested in this curriculum. There is no doubt that uncertainty in a classroom makes students uncomfortable. They like having tasks that make it easy for them to walk the road to success. But, if we keep teaching students entrepreneurship that only works in a classroom, and not in the real world, we aren’t doing them any favors. In fact, we’re setting them up to fail themselves and their employer.

It is our responsibility to push students to fight through difficulty and uncertainty. If your students are uncomfortable, that’s a good thing. When they enter into the workforce, they will be armed with an entrepreneurial mindset, arguably the most important key to success in business over the next 20 years. The great thing about the attendees of the NACCE conference is that most of them already know these two potential barriers to the cultivation of innovative thinking. Many of the educators there were some of the most forward thinking teachers I have met, focused on continuously improving their game and the value they were delivering to students. But classrooms that reflect that understanding remain a small minority. There are still far too many classes making these two big mistakes. Fortunately, I didn’t get booed off stage. Many of the educators in the room shared with me the awesome activities they do with their students to give them those butterflies. I’d love to hear more of your examples. How do you create uncertainty for your students or your employees to encourage entrepreneurial thinking? How do you give them butterflies in their stomachs and inspire them to solve problems?